The Platonic solids are alluring. Their purity is so impossible yet their definition so simple that they attract questions to their existence. These questions have captured the imagination of mathematicians for centuries.

Figure courtesy of here

Figure courtesy of here

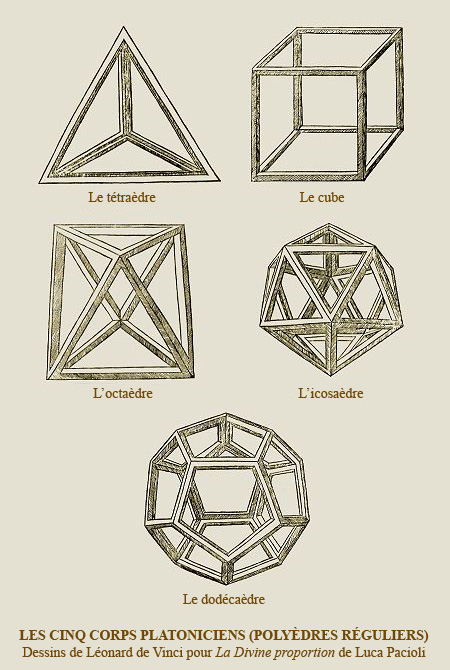

There are can only be five Platonic solids. To be Platonic we require that the faces are congruent and convex regular polygons that meet only at the edges of the object, and each vertex has the same number of faces converging at its point. Although their geometry has been thoroughly exhausted, their history finds these shapes nestled in the minds of the ‘greats’, non-exhaustively including, Euclid, Euler, Da Vinci, Plato, and Kepler. I particularly enjoy Da Vinci’s depictions of the five solids:

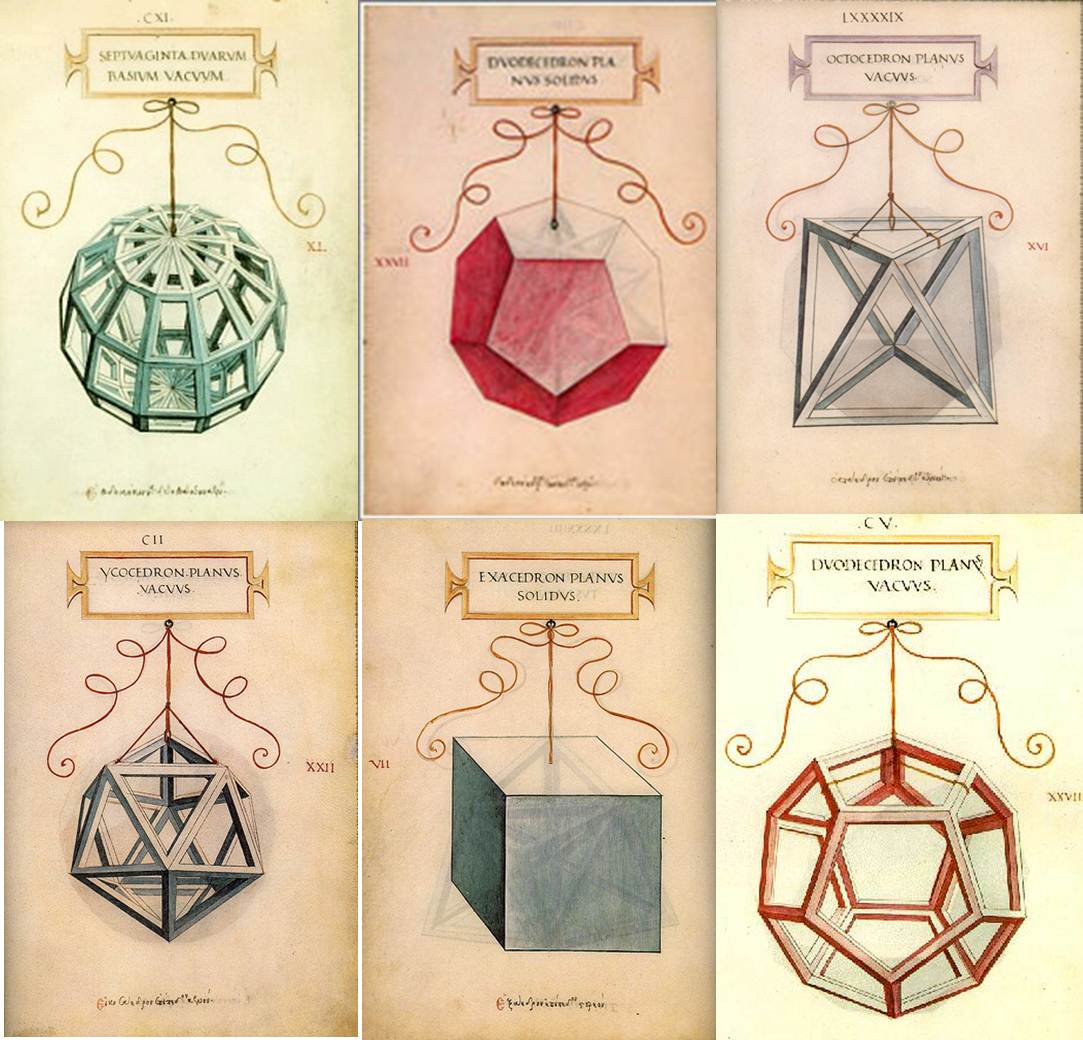

Although not all Platonic, Da Vinci’s other solids are enthralling. These can be found in the book, De Divina Proporione, which Da Vinci illustrated:

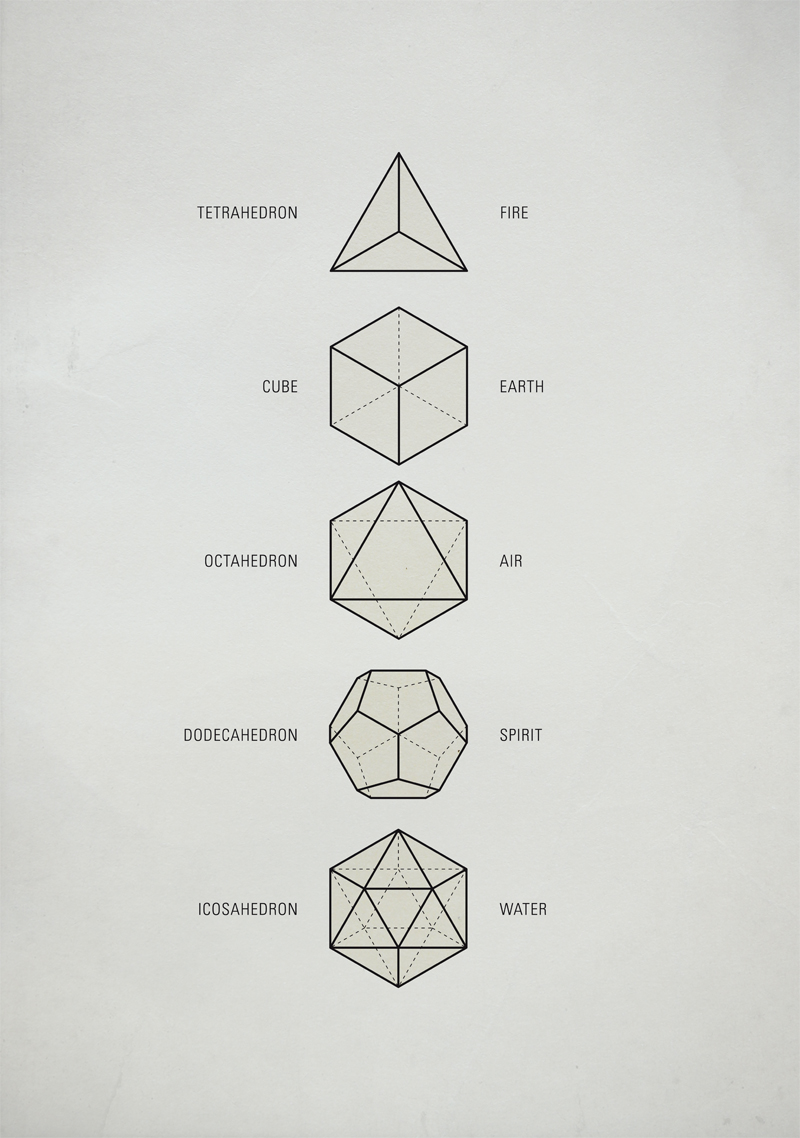

Plato also discusses these solids in his book Timaeus, associating each solid to the five elements of the Universe: earth, air, water, fire, and ‘aether’. Although I haven’t read the work myself, Wikipedia explains it well. The water is the icosahedron because of how it flows, like spherical beads pour through the nooks of a surface. The earth is the cube. Sturdy and brittle, and unforgiving, like the tiling of a cube in a volume. Descriptions of the other three can be found on the Wikipedia page. Illustrating the world through these homogeneous objects is artificial. But instead of disregarding how the past was so wrong about the reality of the Universe, we can be inspired by these representations and try to make them a reality. Picture a system of robotic Platonic solids, a swarm of virus-esque creatures perhaps, coordinating to accomplish tasks such as construction, locomotion, or flight. A self-assembling and self-healing hive.

Johndale Solem has explored the physics behind the self-assembly of Platonic solids. I like to imagine macro-objects composed of these assemblages, which I would call a Platonic Machine as an ode to Plato’s vision of the solids being the reducible essence of creation.

I encourage you to explore the Wikipedia page cited earlier for more interesting stories behind the Platonic and non-Platonic solids. I feel a sci-fi story surfacing around Platonic microbots which I may attempt in the future.